With this article, we will start to go review the caliphate’s history, beginning with the first caliphs that came from Muhammad’s followers and the Umayyad dynasty. But before proceeding with that historical review, there is one more area related to Islam and Muhammad that needs to be discussed. In the last article, Muhammad’s Life and Teachings – Part II, we outlined some of the changes that occurred within Islam’s tenets after the migration to Mecca. Many of the verses within the Qur’an not only changed, but the later revelations themselves conflicted with other verses. These changes produced concern among some of Muhammad’s followers. We’ve already mentioned that some of his followers left Islam shortly after the migration from Mecca to Medina (the Hypocrites cited in Surah 63). We’ve also mentioned the scribe who left Islam after Muhammad allowed him to suggest changes to revelations. This scribe was later ordered to be slain when Muhammad took Mecca.

Along the way we will also look at the development of the Qur’an as it was during this period that it was first collected, written down, and assembled into several codices.

Abrogation

In reply to the concern expressed by his followers concerning the changes and inconsistencies in some of the revelations, Muhammad received the following, ‘Such of Our revelations as We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, we bring (in place) one better or the like. Do not you know that Allah is Able to do all things?’ (S 2.106) Variations of this revelation are repeated in S 13.39 and 16.101. One of Islam’s beliefs is that the Qur’an is an exact replica of a book containing Allah’s eternal word transmitted by the angel Gabriel to Muhammad. Abrogation sets up several inconsistencies within Islam that are difficult to reconcile. We will cover them in more detail later, but for now we will simply mention a couple of them here.

- Islam’s claim that the Qur’an is the final revelation to humankind is undercut. If Allah’s will changes over time, why would this necessarily stop with Muhammad’s death? Indeed we find that other sects later formed within Islam.

- With the changes to the revelations, how does one know that the Qur’an is complete, or that its contents includes the most recent revelations that have not been abrogated as it was not in written form at Muhammad’s death?

Islamic tradition accepts that some items are not included within the Qur’an. These include the verses referred to as the Satanic verses. The Shia also assert that many verses were excluded from the Qur’an by the third caliph Uthman. How can the Qur’an be perfectly preserved unless all revelations have been included?

The Qur’an

It is likely that the Qur’an was never intended to be written, and it had not been collected in written form at Muhammad’s death. In fact the literal meaning of the word is ‘the reading’ or ‘the recital’. This makes sense in a society where many people could neither read nor write. However, within about a year of Muhammad’s death tradition has it that many of his early followers were dead after the battle of Yamamah, and portions of the Qur’an were in danger of being lost.

There are many implications arising from Islam’s tenets. Some of these implications will be discussed later in this series, and some can be found in the following articles.

- Who is Allah?

- Of Allah and Man

- You Will Know Them By Their Fruit

- Sources: A Brief Comparison of the Qur’an and the Bible

- US Law and Shari’a

- Islam and Form of Governance

- Man’s Nature and Islam

The spread of Islam after Muhammad occurred in two waves. The remainder of this article and the next will look at the first wave.

The First Wave

Muhammad left no successor at his death. From Ibn Ishaq’s sirat, ‘Had it not been for what Umar said when he (Muhammad) died, the Muslims would not have doubted that the apostle had appointed Abu Bakr his successor; but he said when he died, “If I appoint a successor, one better than I did so; and if I leave them (to elect my successor) one better than I did so.” So the people knew that the apostle had not appointed a successor and Umar was not suspected of hostility towards Abu Bakr.’ Muhammad’s followers met to discuss who would take his place even before his burial arrangements had been completed. Some argued that Muhammad’s successor should be from his inner circle, and others argued that it should be someone from his blood-line. The first three caliphs came from Muhammad’s inner circle, and the fourth was one of his nephews. The basis of the caliph’s authority was only temporal – not spiritual. He ruled in the name of Islam and upheld Islamic teaching. Bear in mind at this time there was no written Qur’an, nor were there any official doctrines that had been derived yet by the clerics.

- Abu Bakr (632 – 634): Abu Bakr was the father of Aisha, one of Muhammad’s favorite wives. He was chosen by a group of the early converts on the basis of who the Muslims would follow. Khalid ibn-Walid (the Sword of Islam) became general of the army during Bakr’s reign. The Wars of Apostasy were undertaken to more permanently cement the Arabs to Islam, and enforce the payment of tribute. Islam expanded into Gaza and Caesarea.

One tradition has it that Umar requested that the Qur’an be collected after the battle of Yamamah in 633, as many of Muhammad’s early followers who were capable of reciting the Qur’an had died during this battle. Muhammad’s scribe Zayd ibn Thatbit was appointed to collect and assemble all of the verses.

- Umar (634 – 644): Persia and the Eastern Roman Empire had both been greatly weakened by their wars with each other. Umar brought Jerusalem under the control of Islam in 638, and by 641 he had conquered Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Persia. Rome and Persia had fought each other for almost five hundred years, but Persia was no more within ten years after Muhammad’s death. The Arabs were aided by former Persian mercenaries and military slaves that were taken in battle, many of whom had been Monophysite Christians. It is not clear whether they were attracted by the religious aspects of Islam, the cultural ties they shared with the Arab invaders, or merely the attracted by the potential of collecting booty. These converts taught the Islamic leaders new battle tactics and counter-measures. Umar was assassinated by one of his Iraqi slaves in 644.

- Uthman (644 – 656): Uthman consolidated his predecessor’s conquests. He was the first caliph to come from higher order Arab society. This put the Quryash back in control. His reign was marked by nepotism. Uthman was assassinated by rebels, marking the first of the rebellions against divine law. It was during Uthman’s reign that the Medinan codex was selected as the official writing of the Qur’an. All other codices and the variant readings based upon them were ordered to be destroyed. There is more on this topic later in this article.

- Ali (656 – 661): Ali was one of Muhammad’s nephews. He was disliked by Aisha, one of Muhammad’s wives, who conspired with the Governor of Syria to overthrow Ali. The Governor of Syria and Uthman both belonged to the same tribe, the Umayya. Civil war ensued. Ali moved the caliphate’s capital from Medina to Damascus. Ten thousand Muslims died at the ensuing Battle of the Camel, which the forces allied with Ali won. He was assassinated by one of his former supporters. This marked the end of rule by those closely associated with Muhammad and led to the formation of the Umayyad dynasty. Ali’s death also deepened the rift between those who had supported a successor from Muhammad’s inner circle (Sunni) and those who supported a successor from Muhammad’s blood-line (Shia).

The Umayyads (661 – 750)

Mu’awiyah, the Governor of Syria, led the opposition against Ali. He made the position of caliph an inherited one. Ali’s eldest son (Hasan) briefly opposed Mu’awiyah, but then abandoned his claim. Hasan’s brother Husayn went along with the decision as long as Mu’awiyah lived. He refused to recognize his son however, and in 680 he created an anti-caliph state in Iraq. Husayn was defeated and most of his family was killed. This sealed the split between the Sunni and Shia. In 749, the family of the last Umayyad, Marwan, was all killed but one son who fled to Spain.

The Umayyads concerned themselves with acquiring wealth and land. Tradition has it that they had little concern for religious doctrine. They surrounded themselves with palaces, poets, wine, etc. In addition, the armies being maintained required a large revenue stream to support them. Numerous revolts occurred in the later years of the dynasty, the result of internal power struggles. One of the uprisings led to the burning of the Kaaba in Mecca. Shiites, Berbers, and Kharijites all took up arms against the Umayyads, in part because of their second-rate standing in a society where all were supposed to be equal.

Early Development of the Qur’an and Hadith

Within his work Why I Am Not a Muslim, Ibn Warraq goes as far to state that, ‘there is no such thing as the Koran; there never has been a definitive text of this holy book.’[2] However, ‘the ruling power itself was not idle. If it wished an opinion to be generally recognized and the opposition of pious circles silenced, it too had to know how to discover a hadith to suit its purpose. They had to do what their opponents did: invent, and have invented, hadiths in their turn. And that is in effect what they did.’[4] These fraudulent hadith were not rejected by society, but rather, ‘The pious fraud of the inventors of hadith was treated with universal indulgence as long as their fictions were ethical or devotional.’[6]

Four thousand Jews, Christians, and Samaritans were executed in the area from Gaza up to Cesarea in the campaign of 634. The major towns, such as Jerusalem, were not taken as they closed their gates. Towns were usually protected by walls and able to negotiate a treaty with the Islamic army, they became dhimmis. The rural areas were not so fortunate. The later were devastated with crops being set on fire, and peasants massacred or taken as slaves. In 642 the population of Dvin was annihilated, and the Islamic army returned later in the year carrying off 35,000 captives.

The first caliphs were engrossed in conquest. They negotiated with town civic and religious leaders and left military governors to rule the new territories. Initially, Islam was simply viewed as another Jewish or Christian heresy by those countries and provinces it invaded. There were few copies of the Qur’an, and fewer outside of Arabia who could read it, and jihad did not appear to be any different than the razzias (raids) committed by Arab tribes during earlier centuries. As a result the West never fully understood the change that had taken place with the coming of Islam. A mistake that risk repeating today, because we are failing to study and learn the lessons of history.

One example, the prince of Nahavend (located in modern Iran) upon receiving Al-Mughira thought he was being driven to his door by hunger and poverty. He offered to ‘supply you [Al-Mughira] with provisions and you can then go back whence you came.’ In response, Al-Mughira replied that they were fighting in the cause of a prophet that had arose among their people, he had given them revelations that they would receive great victories where they saw such wealth and luxury ‘that those who follow me will not wish to withdraw till it has become theirs.’

Dhimmis

It is during this period that the treatment and status of Dhimmis first solidified. Dhimmi means ‘protected people’. They are the defeated people of the book who do not convert to Islam, and they were required to pay several taxes in addition to a poll tax (jizra). Their protected status only lasted as long as they obeyed the terms of their treaty, or did not offend the Muslims within the area in which they lived.

An early codification of dhimmitude can be found in the Pact of Umar, written by Umar b. Abd al-Aziz in the early 8th century. It states:

‘We shall not build in our cities or in their vicinity any new monasteries, churches, hermitages, or monks’ cells. We shall not restore, by night or by day, any of them that have fallen into ruin or which are located in the Muslims’ quarters.

We shall keep our gates wide open for the passerby and travelers. We shall provide three days’ food and lodging to any Muslims who pass our way.

We shall not shelter any spy in our churches or in our homes, nor shall we hide him from the Muslims.

We shall not teach our children the Qur’an.

We shall not hold public religious ceremonies. We shall not seek to proselytize anyone. We shall not prevent any of our kin from embracing Islam if they so desire.

We shall show deference to the Muslims and shall rise from our seats whenever they sit down.

We shall not attempt to resemble the Muslims in any way . . .

We shall not ride on saddles.

We shall not wear swords or bear weapons of any kind, or ever carry them with us.

We shall not sell wines.

We shall clip the forelocks of our head.

We shall not display our crosses or our books anywhere in the Muslims’ thoroughfares or in their marketplaces. We shall only beat our clappers in our churches very quietly. We shall not raise our voices when reciting the service in our churches, nor when in the presence of Muslims. Neither shall we raise our voices in our funeral processions.

We shall not build our homes higher than theirs.’…

‘Anyone who deliberately strikes a Muslim will forfeit the protection of this pact.’[viii] The taxation and pillaging by the Arabs forced many of these people to flee Muslim lands or go into hiding in the mountains. This deprived the caliph of much of the revenue necessary to support the large army needed to support Islam’s conquests. To protect that revenue, he attached the taxes to the property. At this time, churches were also being converted into mosques.

During the conquests of the first wave, many towns were able to keep most of their religious and political autonomy by simply paying tribute to Medina instead of to Byzantine or Persia, as the Muslims were in the minority from a population perspective. Local Christians or Jews were often left in administrative positions and the Christian Church took on the administration of collecting the tax. Over time Islam moved whole Arab tribes into other areas, a form on colonialization. Eventually, the Arabs were in a position to assume local power, and the administrative positions were filled by Muslims instead of Jews or Christians.

There were several outcomes from the changes under the early caliphate. One, land was seized on the military authority of a tribe that had originated from Mecca, who exercised that military authority through nomadic Arab tribes. Two, the massive Arab emigration created anarchy in the areas where they settled. Three, the method for allocating property and booty between the tribes and Arab state created a perpetual state of bloody conflict, turning previously cultivated areas into wastelands. And four, the inflicting of destruction on the local labor force, the only means of taxation, resulted in drastically diminished revenues for the Umayyad. These led to inter-Arab religious conflicts and a destabilization of the Umayyad. The conflict in goals between different groups also led to the fabrication of the hadith we’ve discussed, and the rise of the Abbisid dynasty that will be the subject of the next article.

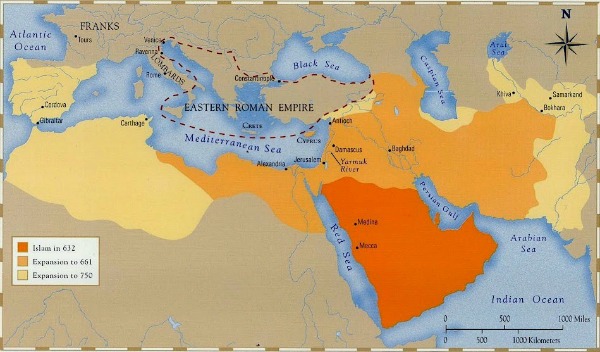

The map below shows the rapid expansion of the caliphate during first 120 years after Muhammad’s death. During this time it conquered an area about the size of the Roman Empire at the height of its power.

[2] Ibid, p. 70.

[4] Goldziher, Ignaz, Introduction to Islamic Theology and Law, p.43, Princeton University Press, 1981.

[6] Ye’or Bat, The Decline of Eastern Christianity under Islam: From Jihad to Dhimmitude, p. 46, Associated University Presses, 1996.

[viii] Ye’or Bat, The Decline of Eastern Christianity under Islam: From Jihad to Dhimmitude, p. 72, Associated University Presses, 1996.

Author and speaker, Dan Wolf, is gifted at gathering facts about contemporary subjects and sharing information in a manner that is easy to read and understand. Dan will be posting both historical and current information about Islam and Sharia on the VCA website.

Author and speaker, Dan Wolf, is gifted at gathering facts about contemporary subjects and sharing information in a manner that is easy to read and understand. Dan will be posting both historical and current information about Islam and Sharia on the VCA website.