SUMMARY: An Egyptian inscription found near the banks of the Nile records the name “Israel.” In this excerpt from the book Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus, Tim Mahoney discusses his visit to the site with Egyptologist David Rohl to discuss the significance of this evidence.

And all the peoples of the earth shall see that you are called by the name of the LORD, and they shall be afraid of you. – Deuteronomy 28:10 (ESV)

Merneptah Stele: The First Mention of Israel in Egypt

Pharaoh Merneptah of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty was the son and successor of Ramesses II. Ramesses was one of Egypt’s most powerful kings and is thought by many to be the pharaoh of the Exodus. But was Ramesses or someone in his family really the pharaoh who thrust the Israelites out of Egypt?

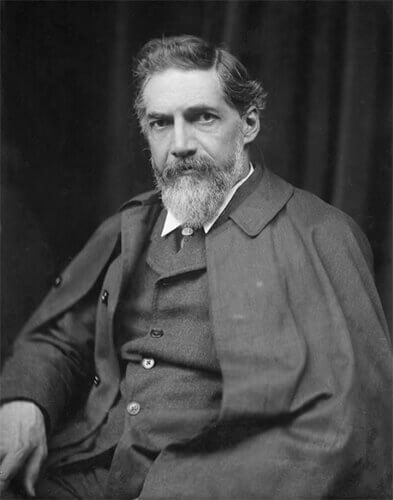

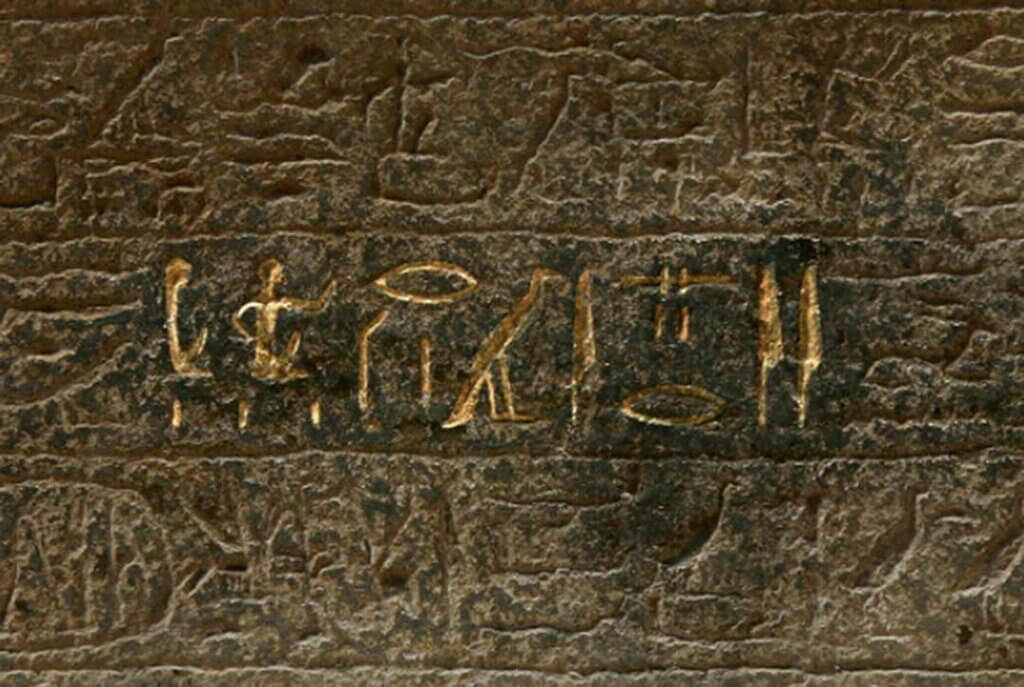

Merneptah is best known for erecting a stone monument, or stele, that mentions the nation of Israel. Commonly called the Merneptah Stele, it was uncovered in 1896 by an English pioneer in Egyptology, Sir Flinders Petrie, who considered it his most important discovery because of its connection to the Bible. The stele was found in King Merneptah’s funerary chapel in Thebes, the ancient Egyptian capital on the west bank of the Nile. On the opposite bank is the Temple of Karnak. The original stele stood here for thousands of years before it was taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. I have filmed at both locations.

Merneptah erected this monument just a few years after his father’s death. Egyptologist David Rohl and many others believe that the victory poem on this stele demonstrates that neither Ramesses II nor his son Merneptah could be the pharaoh of the Exodus. I was anxious to know why.

|

|

———————

Sir Flinders Petrie in 1903. The Merneptah Stele was thought for over a century to be the oldest and only mention of Israel in ancient Egypt. It commemorates Egypt’s victories over its enemies and was erected by Pharaoh Merneptah (1213- 1203 BC) in his 5th year. Recently the Berlin Pedestal has been proposed to have an older mention of Israel. (Petrie: public domain, Merneptah Stele © 2014 Patterns of Evidence, LLC)

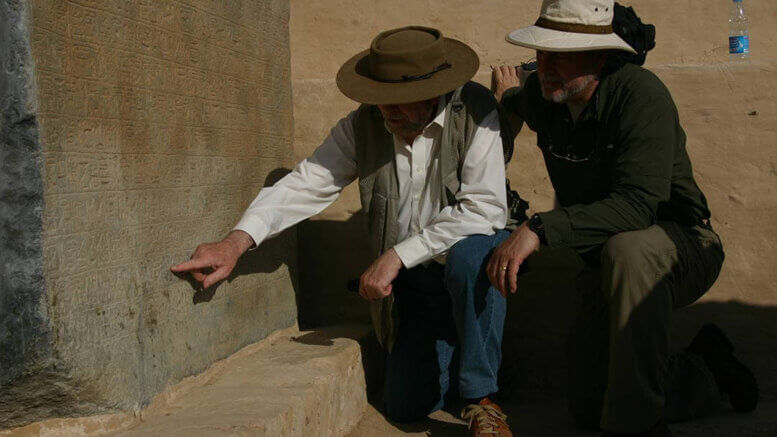

It was 117 degrees Fahrenheit the day Rohl took me to see the Merneptah Stele. I knew it was hot when the Egyptians were looking for shade, but there was no shade as we approached the stele in the open courtyard. In one corner stood the stone artifact with its back against the wall that surrounded the courtyard. Rohl surveyed the ten-foot- high slab. “So this is the famous Merneptah Stele, or what we call the Israel Stele, and it actually belongs to the king, Merneptah. Up there at the top you can see him facing the god Amun.”

“What does it say?” I asked.

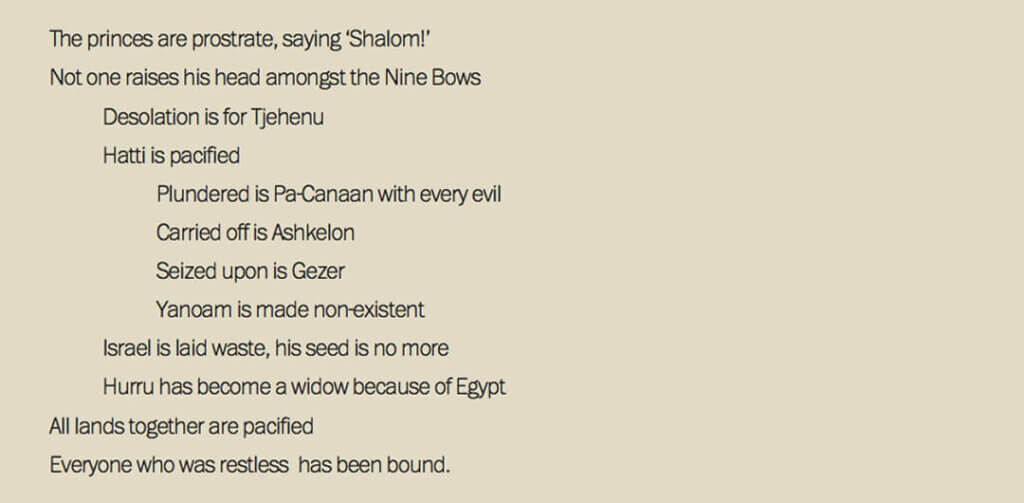

“It’s like a summary of the achievements of the dynasty, and he lists here, in a poetic form, all the different conquered nations, the nations that are at peace. But right at the bottom, you have three crucial lines, because this is where we find a link to the Bible.”

“So that’s why you brought me here?”

Rohl knelt and pointed to the lower portion of the monument. “I brought you here to see this. In particular, one name. You have the two reeds. That’s the sound “e” or “ee”, okay? Then the bolt of cloth, which is “s”, then an “r”, an “a” and an “l”. Is-ra-el.”

“Israel.” I was fascinated. After all I had heard about the lack of biblical evidence, here in the middle of Egypt was an inscription with the name that came from the Bible, Israel.

“Israel,” Rohl echoed. “This is the only time that we see this name on an Egyptian monument.”

“This is very significant, isn’t it?”

“It’s hugely significant.” Rohl then directed me to focus on the hieroglyphs next to the name Israel. “After the name Israel are these two seated figures of a woman and a man, and three strokes underneath.”

“What does that mean?”

Rohl explained, “These three strokes mean plural. So it means the people or nation of Israel. And then this is the interesting bit. It says Fekty bin peret f. That means ‘Israel is laid waste, his seed is no more.’”

“Does it mean that they were literally no more?”

“No. It’s a sort of poetical way of saying they’d been overcome, defeated.”

“Or pacified?” I asked.

“Yes. All these phrases are like that; it’s a poetical phrase effectively.”

The Merneptah Stele and the Ramesses Exodus Date

Rohl continued his argument by directing me to look more closely at the pattern of the “victory poem” on this monument. “What we have are two introductory lines, then we have two major entities, the Libyans and the Hittites, then we have four towns, then we have two more major entities, Israel and Syria. And we finish off with two more lines to close the poem.”

“The way the pattern of the poem works tells us that Israel was a major entity at the time. So it’s effectively the nation of Israel, and it’s out there in the northern part of the world outside Egypt. They seem to be a political entity.”

The reflection of the Egyptian sun off the stele was blinding. Its heat was like a furnace. I could feel sweat trickling down my face. But none of that mattered at this moment. What Rohl had just revealed I knew was very important to this question of whether Ramesses is the pharaoh mentioned in the Bible. “How significant is this then to the story of the Exodus?”

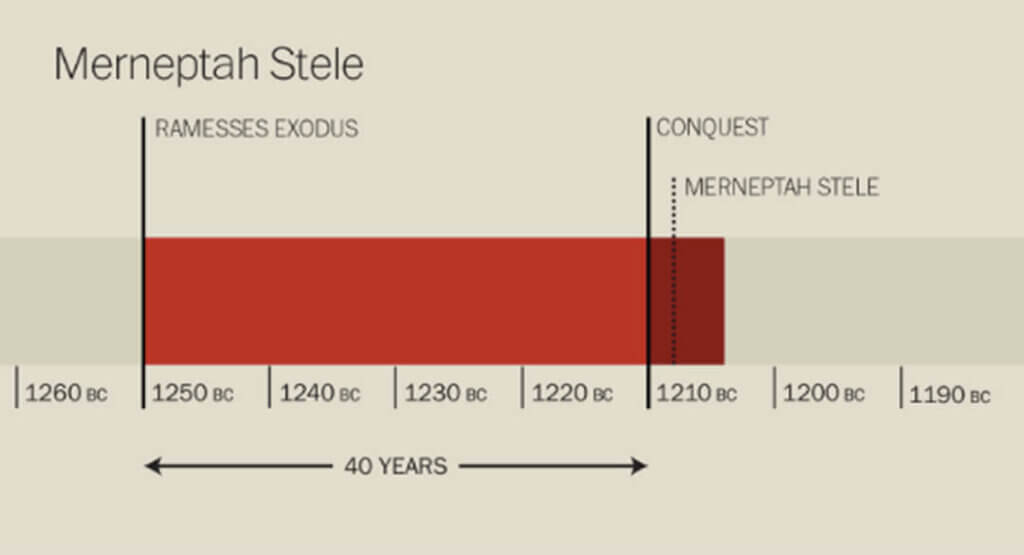

Rohl drew himself up beside the stele and looked at me. “Well, for me it’s very important, because if we’re talking about Ramesses II or Merneptah being at the time of the Exodus with Moses and Joshua, this just doesn’t fit the pattern. It makes no sense at all.”

I could see that this poses a problem for the Ramesses Exodus Theory. The Bible states that the Israelites didn’t even begin to conquer Canaan until 40 years after they left Egypt. So how could Merneptah be the pharaoh of the Exodus if Israel was already established in the land of Canaan by the fifth year of his reign? According to the biblical information, it’s just not possible. (See more on the book Patterns of Evidence: The Exodus)

NOTE: References to the Israelites spending 40 years in the wilderness after the Exodus can be found in Numbers 14:26-34, Deuteronomy 2:7 & 14, and Joshua 5:6. For most of the Judges Period, a span of about 350 years that followed the Conquest, the tribes were fairly independent and not an established and unified nation, sometimes even warring against each other (Judges 20:20).