As Demonstrated in Presidential Inaugurations

Posted May 31, 2010

SOURCE: Wallbuiders

Religious activities at presidential inaugurations have become the target of criticism in recent years, 1 with legal challenges being filed to halt activities as simple as inaugural prayers and the use of “so help me God” in the presidential oath. 2 These critics – evidently based on a deficient education – wrongly believe that the official governmental arena is to be aggressively secular and religion-free. The history of inaugurations provides some of the most authoritative proof of the fallacy of these modern arguments.

————————–

————————–

To sign up on the WallBuilders email list and receive future information about historical issues and Biblical values in the culture, visit http://www.wallbuilders.com/ABTsignup.asp.

—————————

In fact, since America’s first inauguration in 1789 included seven distinct religious activities, that original inauguration is worthy of review. Every inauguration since 1789 has included numerous of those activities.

Constitutional experts abounded at America’s first inauguration. Not only was the first inauguree (George Washington) a signer of the Constitution but numerous drafters of the Constitution were serving in the Congress that organized and directed that first inauguration. In fact, just under one fourth of the members of the first Congress had been delegates to the Convention that wrote the Constitution. 3 Furthermore, the identical Congress that directed and oversaw these inaugural activities also penned the First Amendment.

Having therefore produced both the Constitution and all of its clauses on religion, they clearly knew what types of religious activities were and were not constitutional. Clearly, then, the religious activities that occurred at the first inauguration may well be said to have the approval and imprimatur of the greatest collection of constitutional experts America has ever known. Therefore, a review of the religious activities acceptable in that first inauguration will provide guidance for citizens in general and critics in particular.

The First Inauguration

The first inauguration occurred in New York City. (New York City served as the nation’s capital for the first year of the new federal government; for the next ten, Philadelphia was the capital city; in 1800, the federal government moved to Washington, D. C. for its permanent home). George Washington had been at home at Mt. Vernon when Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Continental Congress, notified him that he had been unanimously elected as the nation’s first president.

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.” 4 Washington did go, and he did indeed fulfill the high destinies assigned him by Heaven. A moving painting was made of her giving him her final charge; his mother passed away a few months after that final meeting.

On receiving this news, Washington departed from Mt. Vernon and began his trek toward New York City, stopping first at Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit his mother, Mary¬ – the last time the two would see each other. Mary was eighty-two and suffering from incurable breast cancer. Mary parted with her son, giving him her blessings and offering him her prayers, telling him: “You will see me no more; my great age and the disease which is rapidly approaching my vitals, warn me that I shall not be long in this world. Go, George; fulfill the high destinies which Heaven appears to assign to you; go, my son, and may that Heaven’s and your mother’s blessing be with you always.” 4 Washington did go, and he did indeed fulfill the high destinies assigned him by Heaven. A moving painting was made of her giving him her final charge; his mother passed away a few months after that final meeting.

Leaving his mother, Washington continued northward toward New York City. In town after town along the way, special dinners and celebrations were held – including in Alexandria, Georgetown, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Trenton, and other locations. Finally reaching Elizabethtown, New Jersey, Washington boarded a barge that carried him the rest of the way, where another celebration awaited him upon entering New York Harbor.

On April 30th, 1789, George Washington was to be inaugurated on the balcony outside Federal Hall. (Federal Hall was originally named Old Hall, but New York City – in an effort to convince the new federal government that the City was serious about becoming the national capital – remodeled the structure, renaming it Federal Hall. The House and Senate met in two chambers inside that Hall, and the inauguration took place on the remodeled building’s balcony.) Incidentally, religious activities had been planned to precede the inauguration, with the people of New York City being called to a time of prayer. The papers in the Capital City reported on that scheduled activity:

[O]n the morning of the day on which our illustrious President will be invested with his office, the bells will ring at nine o’clock, when the people may go up to the house of God and in a solemn manner commit the new government, with its important train of consequences, to the holy protection and blessing of the Most high. An early hour is prudently fixed for this peculiar act of devotion and . . . is designed wholly for prayer. 5

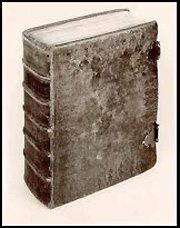

The preparations for the inauguration had been extensive; everything had been well planned; the event seemed to be proceeding smoothly. The parade carrying Washington by horse-drawn carriage to the swearing-in was nearing Federal Hall when it was realized that no Bible had been obtained for administering the oath. Parade Marshal Jacob Morton hurried to the nearby Masonic Lodge and grabbed its large 1767 King James Bible.

The Bible was laid upon a crimson velvet cushion (held by Samuel Otis, Secretary of the Senate) and, with a huge crowd gathered below watching the ceremony on the balcony, New York Chancellor Robert Livingston was to administer the oath of office. (Robert Livingston had been one of the five Founders who had drafted the Declaration of Independence; however, he was called back to New York to help his State through the Revolution before he could affix his signature to the very document he had helped write. As Chancellor, Livingston was the highest ranking judicial official in New York.) Beside Livingston and Washington stood several distinguished officials, including Vice President John Adams, original Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, Generals Henry Knox and Philip Schuyler, and a number of others. The Bible was opened at random to the latter part of Genesis; Washington placed his left hand upon the open Bible, raised his right, and then took the oath of office prescribed by the Constitution. Washington then bent over and kissed the Bible, reverently closed his eyes, and said, “So help me God!” Chancellor Livingston then proclaimed, “It is done!” Turning to the crowd assembled below, he shouted, “Long live George Washington – the first President of the United States!” That shout was echoed and re-echoed by the crowd below.

The Bible was laid upon a crimson velvet cushion (held by Samuel Otis, Secretary of the Senate) and, with a huge crowd gathered below watching the ceremony on the balcony, New York Chancellor Robert Livingston was to administer the oath of office. (Robert Livingston had been one of the five Founders who had drafted the Declaration of Independence; however, he was called back to New York to help his State through the Revolution before he could affix his signature to the very document he had helped write. As Chancellor, Livingston was the highest ranking judicial official in New York.) Beside Livingston and Washington stood several distinguished officials, including Vice President John Adams, original Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, Generals Henry Knox and Philip Schuyler, and a number of others. The Bible was opened at random to the latter part of Genesis; Washington placed his left hand upon the open Bible, raised his right, and then took the oath of office prescribed by the Constitution. Washington then bent over and kissed the Bible, reverently closed his eyes, and said, “So help me God!” Chancellor Livingston then proclaimed, “It is done!” Turning to the crowd assembled below, he shouted, “Long live George Washington – the first President of the United States!” That shout was echoed and re-echoed by the crowd below.

Critics today claim that George Washington never added “So help me God!” to his oath 6 – that associating religious intent with the oath is of recent origins. After all, the presidential oath of office as prescribed in Article II of the Constitution simply states:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.

But overlooked by many today is the fact that the Framers of our government considered an oath to be inherently religious – something George Washington affirmed when he appended the phrase “So help me God” to the end of the oath. In fact, it was universally acknowledged by every American legal scholar of that day that any legally-binding oath was overtly religious in nature. As signer of the Declaration John Witherspoon succinctly explained:

An oath is an appeal to God, the Searcher of Hearts, for the truth of what we say and always expresses or supposes an imprecation [a calling down] of His judgment upon us if we prevaricate [lie]. An oath, therefore, implies a belief in God and His Providence and indeed is an act of worship. . . . Persons entering on public offices are also often obliged to make oath that they will faithfully execute their trust. . . . In vows, there is no party but God and the person himself who makes the vow. 7

Signer of the Constitution Rufus King similarly affirmed:

[B]y the oath which they [the laws] prescribe, we appeal to the Supreme Being so to deal with us hereafter as we observe the obligation of our oaths. The Pagan world were and are without the mighty influence of this principle which is proclaimed in the Christian system – their morals were destitute of its powerful sanction while their oaths neither awakened the hopes nor fears which a belief in Christianity inspires. 8

James Iredell, a ratifier of the Constitution and a U. S. Supreme Court justice appointed by George Washington, also confirmed:

According to the modern definition [1788] of an oath, it is considered a “solemn appeal to the Supreme Being for the truth of what is said by a person who believes in the existence of a Supreme Being and in a future state of rewards and punishments according to that form which would bind his conscience most.” 9

The great Daniel Webster – considered the foremost lawyer of his time 10 – also declared:

“What is an oath?” . . . [I]t is founded on a degree of consciousness that there is a Power above us that will reward our virtues or punish our vices. . . . [O]ur system of oaths in all our courts, by which we hold liberty and property and all our rights, are founded on or rest on Christianity and a religious belief. 11

Clearly, at the time the Constitution was written, an oath was a religious obligation. George Washington understood this, and at the beginning of his presidency had prayed “So help me God” with his oath; at the end of his presidency eight years later in 1796 in his “Farewell Address,” he reaffirmed that an oath was religious when he pointedly queried:

[W]here is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths . . . ? 12

Numerous other authoritative sources affirm that oaths were inherently religious. 13

The evidence is clear: from a constitutional viewpoint, the administering of a presidential oath was the administering of a religious obligation – something that was often acknowledged during presidential inaugurations following Washington’s. For example, during his 1825 inauguration, John Quincy Adams declared:

I appear, my fellow-citizens, in your presence and in that of Heaven to bind myself by the solemnities of religious obligation to the faithful performance of the duties allotted to me in the station to which I have been called. 14

Subsequent presidents made similar acknowledgments:

HERBERT HOOVER: This occasion is not alone the administration of the most sacred oath which can be assumed by an American citizen. It is a dedication and consecration under God to the highest office in service of our people. 15

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT: As I stand here today, having taken the solemn oath of office in the presence of my fellow countrymen – in the presence of our God . . . 16

JOHN F. KENNEDY: For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forebears prescribed nearly a century and three quarters ago. 17

RICHARD NIXON: I have taken an oath today in the presence of God and my countrymen to uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States. 18

There were others as well. 19 The taking of the presidential oath is a religious action – or what Founding Father John Witherspoon had called “an act of worship.” 20

Returning to Washington’s inauguration, following the taking of the oath on the Bible, Washington and the officials then departed the balcony and went inside Federal Hall to the Senate Chamber where Washington delivered his Inaugural Address. From the outset of that first-ever presidential address, Washington – as his first very official act – set a religious tone by expressing his own heartfelt prayer to God:

Such being the impressions under which I have – in obedience to the public summons – repaired to [arrived at] the present station, it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being Who rules over the universe, Who presides in the councils of nations, and Whose providential aids can supply every human defect – that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes. 21

The remainder of Washington’s address was no less strongly religious; he even called on his listeners to remember and acknowledge God:

In tendering this homage [act of worship] to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow-citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of Providential Agency; and in the important revolution just accomplished in the system of their united government [i.e., the creation and adoption of the Constitution] . . . cannot be compared with the means by which most governments have been established without some return of pious gratitude. . . .

These reflections, arising out of the present crisis, have forced themselves too strongly on my mind to be suppressed. . . . [T]he foundation of our national policy will be laid in the pure and immutable principles of private morality . . . since there is no truth more thoroughly established than that there exists in the economy and course of nature an indissoluble union between virtue and happiness – between duty and advantage – between the genuine maxims of an honest and magnanimous policy and the solid rewards of public prosperity and felicity; since we ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious [favorable] smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained. . . .

Having thus imparted to you my sentiments as they have been awakened by the occasion which brings us together, I shall take my present leave; but not without resorting once more to the benign Parent of the Human Race in humble supplication that . . . His divine blessing may be equally conspicuous in the enlarged views, the temperate consultations, and the wise measures on which the success of this government must depend. 22

Washington and the Members of Congress then marched in a procession to St. Paul’s Church for Divine Service. That Congress should have gone to church en masse as part of the inauguration was no surprise, for Congress had itself scheduled these inaugural services.

That is, while the new Constitution had established the presidency, it stipulated nothing specific about the inaugural activities. It was therefore within the authority of Congress to help direct those activities. The Senate therefore acted:

Resolved, That after the oath shall have been administered to the President, he – attended by the Vice-President and members of the Senate and House of Representatives – proceed to St. Paul’s Chapel to hear Divine service. 23

The House quickly approved the same resolution. 24 Once the presidential oath had been administered and the inaugural address delivered, according to official congressional records:

The President, the Vice-President, the Senate, and House of Representatives, &c., then proceeded to St. Paul’s Chapel, where Divine Service was performed by the chaplain of Congress. 25

The service at St. Paul’s was conducted by The Right Reverend Samuel Provoost – the Episcopal Bishop of New York, who had been chosen chaplain of the Senate the week preceding the inauguration. The service was performed according to The Book of Common Prayer, and included a number of prayers taken from Psalms 144-150 as well as Scripture readings and lessons from the book of Acts, I Kings, and the Third Epistle of John. 26

The service at St. Paul’s was conducted by The Right Reverend Samuel Provoost – the Episcopal Bishop of New York, who had been chosen chaplain of the Senate the week preceding the inauguration. The service was performed according to The Book of Common Prayer, and included a number of prayers taken from Psalms 144-150 as well as Scripture readings and lessons from the book of Acts, I Kings, and the Third Epistle of John. 26

The very first inauguration – conducted under the watchful eye of those who had framed our government and written its Constitution – incorporated numerous religious activities and expressions. That first inauguration set the constitutional precedent for all other inaugurations; and the activities from that original inauguration that have been repeated in whole or part in every subsequent inauguration include:

(1) the use of the Bible to administer the oath;

(2) the religious nature of the oath and including “So help me God”; (3) inaugural prayers by the president;

(4) religious content in the inaugural addresses;

(5) the president calling the people to pray or acknowledge God;

(6) inaugural worship services; and

(7) clergy-led inaugural prayers.

1. A number of legal authorities, university professors, and news writers have criticized inaugural religious activities. See, for example, Alan M. Dershowitz, “Bush Starts Off by Defying the Constitution,” Los Angeles Times, Wednesday, January 24, 2001 Metro section, Part B, p. 9; Larry Judkins, Religion Page Editor, Sacramento Valley Mirror, “Dershowitz Piece Misleading: All Presidents Flaunt Constitution,” in Positive Atheism Magazine, Thursday, January 25, 2001 (at: http://www.positiveatheism.org); “President Bush Announces Religious Agenda on Inauguration Day,” Americans United for Separation of Church and State, January 20, 2001 (at: http://www.au.org/site/News2?abbr=pr&page=NewsArticle&id=6095); et. Al. (Return)

2. Noted atheist Michael Newdow filed suit in federal court to have prayers barred from the Presidential Inauguration of 2001, 2005, and in 2009 to have inaugural prayers halted and to prevent the Chief-Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court from saying “So help me God” when administering the oath of office to the president. (Return)

3. Significantly, many of the U. S. Senators at the first Inauguration had been delegates to the Constitutional Convention that framed the Constitution including William Samuel Johnson, Oliver Ellsworth, George Read, Richard Bassett, William Few, Caleb Strong, John Langdon, William Paterson, Robert Morris, and Pierce Butler; and many members of the House had been delegates to the Constitutional Convention, including Roger Sherman, Abraham Baldwin, Daniel Carroll, Elbridge Gerry, Nicholas Gilman, Hugh Williamson, George Clymer, Thomas Fitzsimmons, and James Madison. (Return)

4. Benson J. Lossing, Our Country: A Household History for All Readers (New York: Henry J. Johnson, 1877), Vol. IV, p. 1121. (Return)

5. The Daily Advertiser, New York, Thursday, April 23, 1789, p. 2. (Return)

6. See, for example, Newdow v. Roberts, complaint filed by Newdow on December 29, 2008, pp. 20-21, par. 103-104 of the complaint. See also Cathy Lynn Grossman, “No proof Washington said ‘so help me God’ – will Obama,” USA Today, January 9, 2009 (at: http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2009-01-07-washington-oath_N.htm). (Return)

7. John Witherspoon, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), Vol. VII, pp. 139-140, 142, from his “Lectures on Moral Philosophy,” Lecture 16 on Oaths and Vows. (Return)

8. Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821, Assembled for the Purpose of Amending The Constitution of the State of New York (Albany: E. and E. Hosford, 1821), p. 575, Rufus King, October 30, 1821. (Return)

9. Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions, on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington: 1836), Vol. IV, p. 196, James Iredell, July 30, 1788. (Return)

10. Dictionary of American Biography, s. v. “Webster, Daniel.” (Return)

11. Daniel Webster, Mr. Webster’s Speech in Defense of the Christian Ministry and in Favor of the Religious Instruction of the Young, Delivered in the Supreme Court of the United States, February 10, 1844, in the Case of Stephen Girard’s Will (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1844), pp. 43, 51. (Return)

12. George Washington, Address of George Washington, President of the United States . . . Preparatory to His Declination (Baltimore: George and Henry S. Keatinge, 1796), p. 23. (Return)

13. See, for example, James Coffield Mitchell, The Tennessee Justice’s Manual and Civil Officer’s Guide (Nashville: Mitchell and C. C. Norvell, 1834), pp. 457-458; see also City Council of Charleston v. S.A. Benjamin, 2 Strob. 508, 522-524 (Sup. Ct. S.C. 1846); and many other legal sources. (Return)

14. John Quincy Adams, Messages and Papers of the Presidents, James D. Richardson, editor (Washington, D.C.: 1900), Vol. 2, p. 860, March 4th 1825. (Return)

15. Public Papers of the Presidents, Herbert Hoover, 1929, p.1, March 4th, 1929. See also Herbert Hoover, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, March 4, 1929 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=21804). (Return)

16. < i>Public Papers of the Presidents, F. D. Roosevelt, 1944, Item 7, January 20th, 1945. See also Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, January 20, 1945 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=1660). (Return)

17. Public Papers of the Presidents, J. F. Kennedy, 1961, p.1, January 20th, 1961. See also John F. Kennedy, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, January 20, 1961 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8032). (Return)

18. Public Papers of the Presidents, Nixon, 1969, p.3-4, January 20th, 1969. See also Richard Nixon, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, January 20, 1969 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=1941). (Return)

19. See, for example, Warren G. Harding, Inaugural Address, March 4, 1921; and Public Papers of the Presidents, Jimmy Carter, 1977, p.1, January 20th, 1977. See also Warren G. Harding, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, March 4, 1921 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=25833); Jimmy Carter, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, January 20, 1977 (at: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=6575). (Return)

20. John Witherspoon, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), Vol. VII, p. 139, from his “Lectures on Moral Philosophy,” Lecture 16 on Oaths and Vows. (Return)

21. The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States, Joseph Gales, editor (Washington: Gales & Seaton, 1834), Vol. I, p. 27. See also George Washington, Messages and Papers of the Presidents, James D. Richardson, editor (Washington, D.C.: 1899), Vol. 1, pp. 44-45, April 30, 1789. (Return)

22. Debates and Proceedings (1834) Vol. I, pp. 27-29, April 30, 1789. (Return)

23. Debates and Proceedings (1834), Vol. I, p. 25, April 27, 1789. (Return)

24. Debates and Proceedings (1834), Vol. I, p. 241, April 29, 1789. (Return)

25. Debates and Proceedings (1834) Vol. I, p. 29, April 30, 1789. (Return)

26. Book of Common Prayer (Oxford: W. Jackson & A. Hamilton, 1784), s.v., April 30th. (Return)