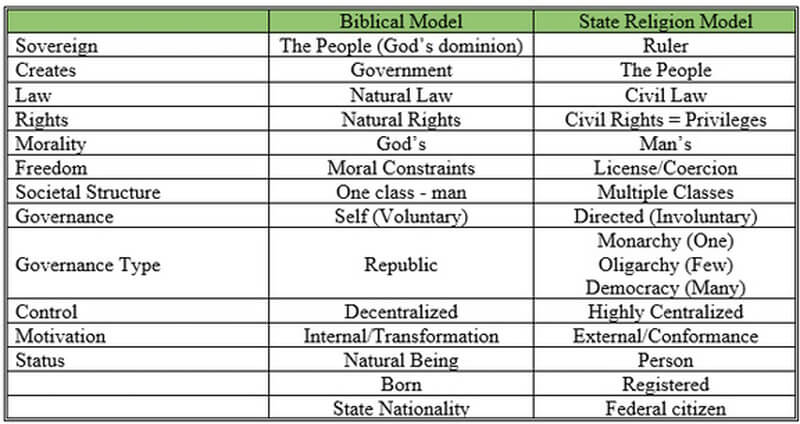

Last time we looked at two governance models, some of their differences, and a few implications. One foundational difference is in the law. This time I will list some of the foundational ideas underlying both societies, and tie those to implications coming from them. The list won’t cover everything, but will set the stage for discussing America, both its founding and how it changed to what we have today. These set the stage for examining critical theory and demonstrating its use with Christian nationalism.

Foundational Ideas

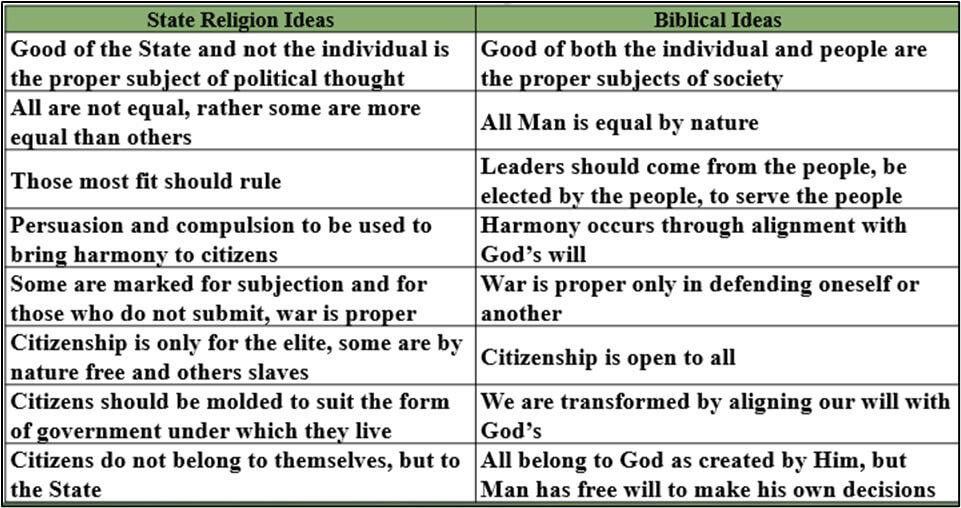

Below are some foundational ideas from each governance model in the last article. These could just as well be called principles. Each are listed, with their references. Afterward, we’ll compare them. The models presented last time are incompatible as their underlying ideas cannot co-exist.

Biblical Model

- The good of the individual and their people are the proper object of Society. (1 Pet. 2:9)

- There exists a common set of rights, and shared commitment to the common good.[1]

- All are equal by natural (internal equality). We have a shared ancestry to Adam and Eve. (Gen. 1:26-8, Gal. 3:28)

- Leaders should come from the people, be elected by the people, in order to serve the people—and thereby serve God. (Deut. 1:13-9)

- Peace and harmony within society comes through people’s alignment with God’s will. (Isaiah 14 and 55, Jeremiah or any of the prophets, 1 Tim. 6:2-4, Rom. 8:26-8)

- War is proper only in defending oneself or another.[2] (Ex. 20:13, Gen. 6:5-7)

- Citizenship in this country is open to all. (Gal. 3:28)

- We are transformed by aligning our will with God’s, through the renewing of our mind. (Rom. 12:2)

- All belong to God through His act of creation. However, man has the free will to choose whether he aligns with God’s will or goes his own way. (Deut. 30:15-9)

State Governance

- The good of the state is supreme to the good of the people.[3]

- All are not equal, but rather some are more equal than others.[4]

- Equality is based upon outward appearances; wealth, power, family, position, etc.

- Within these societal classes, there must be at least one with the attributes needed to rule. Therefore, these should rule.[5]

- Rome, for example. Ruling classes such as the senators, equestrians, and patricians. Plebian classes had their own law, elections, etc., but did not participate in Rome’s governance.

- Societal harmony is important, and the state should use persuasion and/or compulsion to create it.[6]

- Some are meant to rule and others serve.[7] For those who will not submit, war is proper.[8]

- Citizenship is only for the elite, those freed from the drudgery of manual labor.[9]

- Citizens should be molded to fit the state’s needs.[10]

- State control of public education, media, music, literature, poetry, history, etc.

- Citizens do not belong to themselves, but to the state.[11]

- People are property without rights—a special class of slaves.

A Comparison

Putting these ideas side by side shows the stark contrast between them. We can only choose one set or the other.

Some Implications

Heaven is Our Native Country

Citizenship within the Biblical model is open to all. If you look at the Biblical model’s ideas, you’ll see they present different principles for God’s people from the perspective of a country. Jonathan Edwards thought this as well. The following excerpts are from one section of a sermon referenced as Sermon XIII[12]. The sermon’s foundational scripture comes from 1 Pet. 2:9.

Edwards opens with how Christian’s beliefs differ. He then moves on to how Christians are both a royal priesthood and kings. However, “The two offices of king and priest were accounted very honourable both among Jews and heathens; but it was a thing not known under the law of Moses, that the same person should sustain both those offices in a stated matter.”[13]

Christ is spoken of as “a priest after the order of Melchizedek.”[14] Both king and priest. “The reward of the saints [Christians] is represented as a kingdom, because the possession of a kingdom is the height of human advancement in this world, and as it is the common opinion that those who have a kingdom have the greatest possible happiness. The happiness of a kingdom, … consists in these things:

‘First. The honour of a kingdom.

‘Secondly. The possessions of kings.

‘Thirdly. The government or authority of kings.”[15]

We are to well execute our office. “Be ready to distribute, willing to communicate, and do good; consider it as part of your office thus to do, to which you are called and anointed, and as a sacrifice well-pleasing to God; pity others in distress; be ready to help one another; God will have mercy and not sacrifice.”[16]

The Christian Nation

As a First Great Awakening leader, Edward’s ideas influenced America’s Founders and their parents. He describes Christians as a holy nation. While on earth, we are ambassadors rather than natives. Just like ambassadors, we have responsibilities and duties we owe to our true homeland. Further attributes include;

- “First. The saints are all of the same native country. Heaven is the native country of the church. They are born from above.”[17]

- “Secondly. All Christians speak the same language. They all profess the same fundamental doctrines; hold fast the form of sounds that was once delivered to the saints.”

- “Thirdly. They are under the same government. The Christians are one society, one body politic; and therefore, as here the church is represented by a nation, so oftentimes is it called a city They are subject to the same King, Jesus Christ. He is the head of the church, he is the head of this body politic. Indeed all men are subject to the power and providence of this King.”[18]

Its Governance

- “They are all governed by the same laws, and all subject themselves to the same rules. The commands of God that are obeyed by the saints, are the same all over the world. There is the same method of government, there are the same means of government, the same outward and visible means, the same officers, gospel, and gospel ministers, in like manner appointed and sent forth by the head of the church, the same visible order and discipline appointed for all.”[19]

- “[N]ow is there free liberty to any to come and join themselves to this nation, and they shall be received and admitted to the same rights and privileges, and be in all respects treated as the same people.”[20]

- “This nation is governed by the most wise and righteous laws.”[21]

- “This nation is a free people. The happy government under which they live, is most consistent with freedom; it does not in the least infringe upon the liberty of the subject, there is nothing like slavery in the kingdom of God. The law of this nation is a law of liberty.”[22]

- “There is no nation that dwell in such love and peace as this holy nation enjoys. The happiness of a people very much consists in its peace; a nation is never more miserable than when it is rent by civil wars, or disturbed by intestine broils.”[23]

A Brief List

Before closing, the following is a partial list of other implications from the ideas embodied in each governance model. This serves as a natural point to stop, and sets up the discussion of America’s founding and corruption. It’s corruption will in turn lead to critical theory, and that theory’s use related to the Christian nationalist label.

For more on state nationality.[24] Once again, the above implications could not be any further apart, and it all stems from the difference in each model’s underlying ideas. Ideas do indeed have consequences.

Footnotes:

[1] Walsh, Gerald et al, p. 224, Augustine, City of God, Doubleday Publishing, 1958. Book XI, Chap. 16. Also see Schaff, Philip, p. 35, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Volume 2, Augustin: City of God, Christian Doctrine, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989. Book II, Chap. 21.

[2] Schaff, Philip, p. 407-9, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Volume 2, Augustin: City of God, Christian Doctrine, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989. Book XVI, Chap. 12.

[3] Barnes, Jonathan, Ed., p. 2101, The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, Volume II, Princeton University Press, 1995. Politics, VII, II.

[4] Ibid, p. 1991, Politics, I, VI.

[5] Ibid, p. 2044, Politics, III, XVII.

[6] Cooper, John, Ed., p. 1137, Plato: Complete Works, Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1997.

[7] Barnes, Jonathan, Ed., p. 1990, The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation, Volume II, Princeton University Press, 1995. Politics, I, V.

[8] Ibid, p. 1992, Politics, I, VII.

[9] Ibid, p. 2028, Politics, III, V.

[10] Ibid, p. 2121, Politics, VIII, I.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Edwards, Jonathan, pp. 936-949, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, Volume 2, Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. 2006.

[13] Ibid, p. 940.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid, p. 941.

[16] Ibid, p. 944.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid, p. 945.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] GPO Style Manual, p. 95, Section 5.23, Government Publishing Office, 2016.