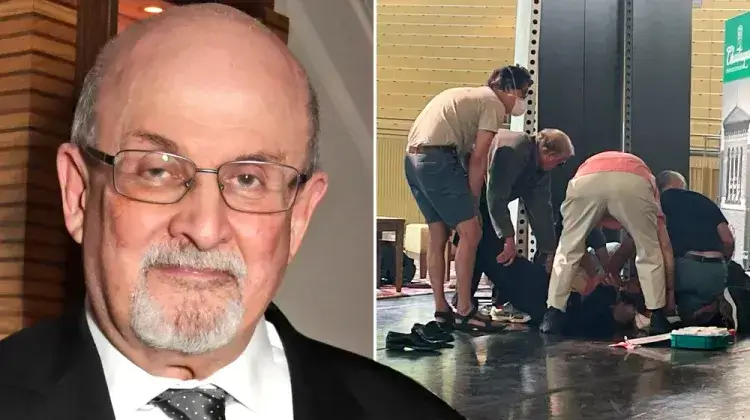

Last Friday, a Muslim man lunged at and repeatedly stabbed Salman Rushdie as he was preparing to deliver a speech on a New York stage. Prosecutors said the author was stabbed 10 times, suffering a neck wound, liver damage, a severed nerve in his arm, and may well lose an eye. Thankfully, reports Sunday morning indicate Rushdie is off a ventilator and able to speak.

Rushdie became internationally recognizable in 1988, following the publication of his novel, The Satanic Verses. Because it portrayed the Muslim prophet of Islam irreverently, the book provoked ire throughout the Muslim world, culminating with a 1989 fatwa calling for his execution as a blasphemer by Iran’s then supreme leader, Ayatollah Khomeini.

In other words, Friday’s assassination attempt against Rushdie has been nearly 35 years in the making and should surprise no one.

And yet, those most charged with explaining events to the rest of us, the so-called “mainstream media,” are still and rather predictably searching for a “motive”—not least since reporting the full truth may make Islam look “bad.”

Back in the real world, Muslim attacks on those perceived to “blaspheme” against Islam’s prophet have a long and unvaried history that stretches straight back to Muhammad himself. Yes, the prophet of Islam was the first Muslim to call for and therefore legitimize the assassination of those who mocked him, saying doing so was “God’s work.”

Thus, when Ka‘b ibn Ashraf, an elderly Jewish leader, mocked Muhammad, the prophet exclaimed, “Who will kill this man who has hurt Allah and his messenger?” A young Muslim named Ibn Maslama volunteered on condition that he be allowed to deceive Ka‘b to gain his trust in order to get close enough and kill him. Muhammad agreed, and the rest — Ibn Maslama dragged the Jew’s head back to Muhammad to triumphant cries of “Allahu akbar!” — is history.

In another example, after Muhammad learned that Asma bint Marwan, an Arab poetess, was making verse that portrayed him as nothing more than a murdering bandit, he called for her assassination, exclaiming: “Will no one rid me of this woman?” That very night, Umayr, a zealous Muslim, crept into Asma’s home while she lay sleeping surrounded by her young children. After removing one of her suckling babes from her breast, Umayr plunged his sword into the poetess. The next morning at mosque, Muhammad, who was aware of the assassination, said, “You have helped Allah and his Apostle.” Apparently feeling some remorse, Umayr responded, “She had five sons; should I feel guilty?” “No,” the prophet answered. “Killing her was as meaningless as two goats butting heads” (from Muhammad’s earliest biography, Sirat Rasul Allah, p.676).

From here, it becomes clear — except, of course, to the disingenuous and narrative driven media — why, past and present, Muslims have attacked and slaughtered countless people accused of speaking (or writing) against Muhammad. Validating this assertion is almost futile, as blasphemy-related stories surface with extreme regularity (very recent examples come from nations as varied as Greece, India, Afghanistan, and Malaysia). In my monthly Muslim Persecution of Christians series, of which there are some 130 reports stretching back to 2011, virtually every month features several anecdotes of Muslims attacking, possibly murdering, Christians on the mere accusation of blasphemy.

As a recent example, a throng of Muslims stoned and burned to death Deborah Emmanuel, a Christian college student in Nigeria, on the unsubstantiated rumor that she had offended Muhammad. In support of her murder, one Muslim cleric enthusiastically declared, “When you touch the prophet we become mad people…. Anyone who touches the prophet, no punishment — just kill!”

In another especially warped example from earlier this year, a Muslim woman and her two nieces slaughtered a Christian woman in Pakistan, after a relative of the three murderers merely dreamt that the Christian had blasphemed against Muhammad. Between just 1990 and 2012 alone, to say nothing of the last decade, “fifty-two people have been extra-judicially murdered on charges of blasphemy” in Pakistan.

Nor is this matter limited to “vigilante” or overzealous Muslims. Several Islamic nations criminalize any criticism of Muhammad. According to Section 295-C of Pakistan’s penal code, for example,

Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation, or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine.

What explains this phenomenon? Why don’t the followers of other religions respond similarly to those who “blaspheme”? The answer is that few modern religions are as fragile as Islam. Built atop a flimsy and easily collapsed pack of cards, silencing any criticism against its founder — whose words and deeds so easily lend themselves to constant criticism — has always been and remains pivotal to Islam’s survival. Discussing Koran 5:33, which calls for the crucifixion and/or mutilation of “those who wage war against Allah and His Messenger and strive upon earth [to cause] mischief,” the highly revered Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328) — the “Sheikh of Islam” — once wrote:

Muharaba [waging war] is of two types: physical and verbal. Waging war verbally against Islam may be worse than waging war physically — hence the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) used to kill those who waged war against Islam verbally, while letting off some of those who waged war against Islam physically. This ruling is to be applied more strictly after the death of the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him). Mischief may be caused by physical action or by words, but the damage caused by words is many times greater than that caused by physical action; and the goodness achieved by words in reforming may be many times greater than that achieved by physical action. It is proven that waging war against Allah and His Messenger (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) verbally is worse and the efforts on earth to undermine religion by verbal means is more effective (Crucified Again, p. 100).

This is not merely a medieval interpretation or limited to “radical Muslims.” Indeed, returning to the recent Rushdie stabbing, Dr. Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, an Islamic studies academic who teaches at Oberlin College, Ohio, endorsed the fatwa in 1989, because “all Islamic nations and countries agree with Iran that any blasphemous statement against sacred figures should be condemned.”

Considering that Dr. Mahallati is popularly known on Oberlin campus as “the Professor of Peace” should dispel any doubts as to how ironclad the penalty for those who criticize Muhammad is among even his ostensibly “moderate” followers.

SOURCE: RAYMOND IBRAHIM