As Christians prepare to celebrate Easter, Muslims continue to desecrate that one symbol most representative of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ: the Crucifix.

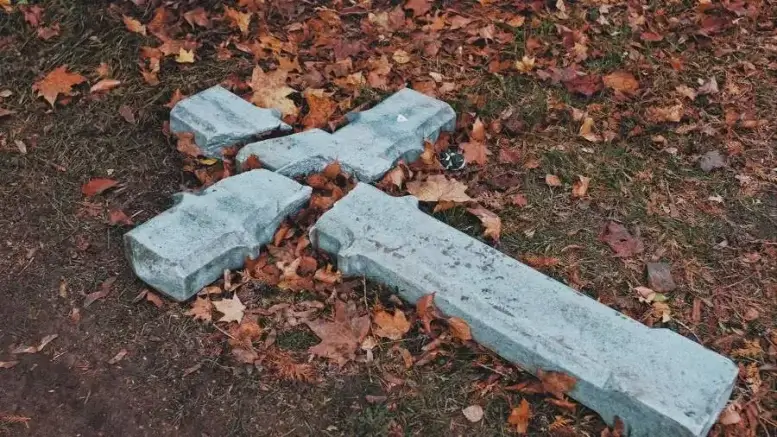

Most recently in France, on Mar. 16, 2023, a Muslim man smashed a church’s six foot tall Plexiglas cross—which had stood since the 1600s—into pieces. A week earlier, also in France, another Muslim man broke off and desecrated the crucifixes affixed to some 30 graves.

A couple weeks before that, in neighboring Belgium, a 16-year-old convert to Islam arrested on terrorist related charges had earlier videotaped himself smashing crucifixes.

What is it about the cross that prompts such behavior?

For starters, not only is it the symbol of Christianity; it also symbolizes the fundamental disagreement between Christians and Muslims. As Historian Sidney Griffith explains, “[t]he cross … publicly declared those very points of Christian faith which the Koran, in the Muslim view, explicitly denied: that Christ was the Son of God and that he died on the cross.” Accordingly, the cross “often aroused the disdain of Muslims,” so that from the start of the seventh century Muslim conquests of Christian lands, there was an ongoing “campaign to erase the public symbols of Christianity, especially the previously ubiquitous sign of the cross.”

Testimonies abound from the very earliest invasions into Christian Syria and Egypt of Muslims systematically breaking every crucifix they encountered. According to Anastasius of Sinai, who lived during the seventh century Arab conquests, “the demons name the Saracens [Arabs/Muslims] as their companions. And it is with reason. The latter are perhaps even worse than the demons,” for whereas “the demons are frequently much afraid of the mysteries of Christ”—among which he mentions the cross—“these demons of flesh trample all that under their feet, mock it, set fire to it, destroy it”

The comparison to demons is not without significance. Last year in Pakistan, for example, a Muslim man named Muhammed climbed atop and wrapped himself around a large cross on church property and started spasmodically swinging his body in an attempt to bring it down—all while reciting Koran verses, shouting Islam’s jihadist war-cry, “Allahu Akbar,” and threatening Christians (video here). According to the report, Muhammad was “in such a religious frenzy,” and so “intent to tip the cross over,” that “he was risking his life to do so.” He fell, was injured and tended to—by Christians.

Similarly, in France, after a Muslim man was arrested for destroying crosses in a graveyard, initial reports stated that “The man repeats Muslim prayers over and over, he drools and cannot be communicated with: his condition has been declared incompatible with preliminary detention.” He was hospitalized as “mentally unbalanced.”

Ironically, for Muslims, it is the cross itself that it satanic. After referring to the crucifix as “an element of the devil,” Indonesian cleric Sheikh Abdul Somad continued his videotaped response to the question why Muslims “felt a chill whenever they saw a crucifix,” by saying, “Because of Satan!” Similarly, Kuwaiti cleric Othman al-Khamis issued a fatwa comparing the Christian crucifix to Satan, adding that crosses can only be publicly displayed in order to mock them, for example by depicting them “in an insulting place such as socks.” In keeping with such logic, a Pakistani shoe-seller placed the image of the cross on the soles of his shoes, so that the crucifix might be trodden with every Muslim footstep.

As with all things Islamic, hate for the cross traces back to the Muslim prophet Muhammad. He reportedly “had such a repugnance to the form of the cross that he broke everything brought into his house with its figure upon it,” to quote historian William Muir. Muhammad also claimed that at the end times, Jesus (the Muslim “Isa”) would make it a point to “break the cross.”

When asked about Islam’s ruling on whether anyone — even a Christian — is permitted to wear a cross, Sheikh Abdul Aziz al-Tarifi, a Saudi expert on sharia, confirmed the hostility: “Under no circumstances is a human permitted to wear the cross.” Why? “Because the prophet — peace and blessings on him — commanded the breaking of it [the cross].”

Sheikh al-Tarifi also explained that if it is too difficult to break the cross — for example, a large concrete statue — Muslims should at least try to disfigure one of its four arms “so that it no longer resembles a cross.” Historic and numismatic evidence confirms that, after the Umayyad caliphate seized the Byzantine treasury in the late seventh century, the caliph ordered that one or two arms of the cross on the stolen Christian coins be effaced so that the image no longer resemble a crucifix.

Fast-forward nearly fourteen centuries, a few years ago in Turkey, authorities “ruled that architectural elements of houses which resemble crosses will not be tolerated.” This ruling came “following complaints that the balconies of certain villas in the village resembled crosses. Photos show that houses had two levels and a cross shape divided the houses into four quadrants. Multiple complaints … led the houses to be destroyed on the basis of their architecture incorporating the cross.”

It is perhaps this continuity between past and present that is most telling. If in 2019 Muslims used human excrement to draw a cross on a French church—smearing fecal matter on churches is not uncommon in the Muslim world—in 1147 in Portugal, Muslims displayed “with much derision the symbol of the cross,” wrote a chronicler. “They spat upon it and wiped the feces from their posteriors with it.” Decades earlier in Jerusalem, Muslims “spat on them [crucifixes] and did not even refrain from urinating on them in the sight of all.” Even that supposedly “magnanimous” sultan, Saladin, commanded “whoever saw that the outside of a church was white, to cover it with black dirt,” and ordered “the removal of every cross from atop the dome of every church in the provinces of Egypt” (Sword and Scimitar, pp. 171, 145, 162).

But why should this topic matter in the first place? After all, the cross is an inanimate object; mocking or destroying it should have zero impact a Christian’s faith. While this is true—and while attacks on real, living humans, chief among them Christian minorities throughout the Muslim world, are obviously worse—attacks prompted by or targeting the cross are important because they truly underscore the reason behind the hate, perhaps even more than when a Muslim kills a Christian (which can be and often is allotted to several other interpersonal factors, for example, personal envy).

Lest all of the above appear too theoretical or abstract, in Part 2 of this article, countless modern day examples of Muslim hostility, violence, and murder provoked by the crucifix will be documented.