This article picks up where we left off last time, and begins with building on the last article’s information. We’ll next look at some shortcomings in the results. These gaps point to the next topic requiring discussion, and that will take place in another article. There is already enough to cover today. This article’s content is not exhaustive, but intended to provide you with a lay of the land.

So Far

Relevant points from previous articles include;

- Man is sovereign as noted in America’s state constitutions.

- Also noted is government’s role as public servants. These support America’s using the Biblical trust model described before. (See below.)

- America’s government incorporated at the federal, state, and local levels.

- The primary reason for incorporating is limiting liability. Why would a people limit government’s liability—its accountability for the dominion given to it?

- Using corporations goes back a long way. Much of today’s corporate law derives from pagan Roman civil law; it’s contrary to America’s founding principles.

- Societies based upon Biblical and pagan principles are mutually exclusive and incompatible. They cannot coexist.

- People are sovereign in Biblical principled societies. They create government. Government’s purpose is protecting our natural rights, supporting the common good, and providing limited services to those ends. Power is limited. Morality exists at the individual and collective level. Society’s basis is self-sacrifice; what can I do for you.

- Pagan principled societies are largely the reverse. The government is sovereign. It creates the people, and government’s purpose is preserving the state. The people exist to support that effort. Power is absolute and unlimited. There is only a collective morality. Society’s basis is self-interest; what can you do for me.

- There are three relevant types of law (jurisdictions) and a priority between them.

- Air is the highest type and relates to trust law. What one receives dominion over.

- Land is the next highest type and relates to common law. It concerns rights and property (title). What an individual has.

- Water (Admiralty) concerns contracts and commerce. What one agrees to with another person (individual or corporation).

- All but a few courts today are administrative, meaning they cover all three jurisdictions.[1]

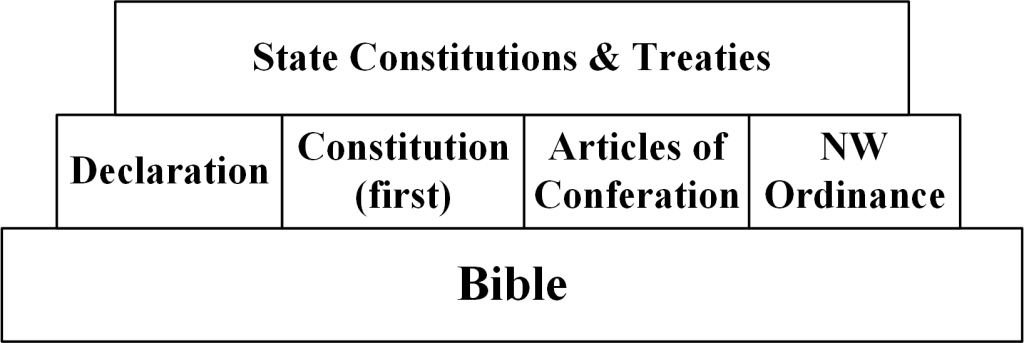

America’s Law Foundation

The diagram below shows America’s law sources. Each layer provides a floor or foundation for those above it. Any layer can use higher standards, but cannot go below those of its foundation. Any law must meet its foundation’s standards, or it is not law—it is void.

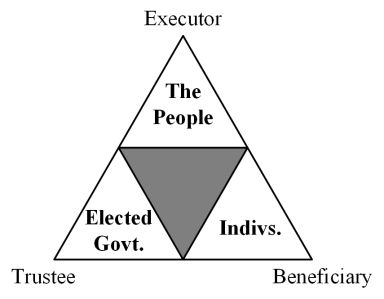

America’s Republic

America’s initial government was a republic; one based upon the Biblical trust model between God and Man as shown below.[2]

Several Problems

America faced several problems when declaring independence from Britain. The first, each colony was separate—independent of the others with their own governance. In a word, sovereign. Our Founders resolved this problem through the system of federalism they created in our initial documents. Each State therefore agreed not to go below the federal standards within those shared areas. However, Biblical principles still served as the underpinning for everything.

The second concerned the people themselves. No one was a New Yorker, Virginian, or North Carolinian at this time. Instead, the colonies contained British, French, Dutch, and other people. Each colony passed naturalization acts during the War for Independence. Virginia passed three such laws before the federal government passed its first one in 1790.

Virginia passed its first naturalization act in 1779. “The act required applicants to give proof, by oath, that they intended to live in Virginia. Applicants also assured the court of their fidelity to the commonwealth. The clerk of the court recorded the oath and issued the applicant a certificate. Foreign citizenship could be relinquished verbally in court or by a deed recorded in court.”[3] Colonists wishing to become New Yorkers, Virginians, or North Carolinians simply provided an oath, which the court then recorded. These individuals became the trust beneficiaries noted above.

Which Constitution?

By 1842, the constitution had three additional amendments. The last is of interest as it is not in the documents we see today. It states any US citizen receiving any title of nobility or honor from a foreign power shall “cease to be a citizen of the United States, and shall be incapable of holding any office of trust.”[4] This article is no longer in the constitution nor mentioned in the online congressional records. It is also of interest as Abraham Lincoln was a member of the BAR (British Accreditation Registry), a title bestowed by a foreign power.

Support

Much of this may seem foreign, and that is okay. Plenty of evidence exists supporting everything mentioned in this series. This section begins to lay out some of that evidence. It is not exhaustive, but simply provides some starting points.

Edward Coke

Common law formed the basis of rights as Englishmen our Founders fought and gave their lives for. Few had greater influence than Edward Coke on our Founders view of common law.

He believed the, “common law was a distillation of common custom, itself unwritten and immemorial. ‘It embodies the wisdom of generations, as a result not of philosophical reflection, but of the accumulations and refinements of experience.’”[5] Societies developed customs, practices, and standards governing themselves. They kept what worked. The creation of bills of exchange replacing carrying large quantities of gold and silver coins in about the 9th century, and the transition of the woolens (and other) industries from manual labor to mechanical methods during the late Middle Ages are just two examples.[6]

Such improvements came from man’s inventiveness at solving problems. The ones benefitting society were kept. Law entered the picture later when someone violated these conventions, or in an instance where everyone followed custom and a bad outcome still resulted. Law played a relatively narrow role supporting society’s development.

One example of Coke’s importance in developing America’s common law. The General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered that “‘to the end we may have the better light for making & proceedings about lawes, that there shalbe … procured for the use of the Courte from time to time’ two copies each of Coke’s First and Second Institutes, Coke’s Reports (I-II), Coke’s Book of Entries, Michael Dalton’s Country Justice, and John Rastell’s Les Terms de la Ley.”[7]

Common Law

Black’s Law Dictionary defines common law as,

“[D]istinguished from statutory law created by the enactment of legislatures, the common law comprises the body of those principles and rules of action, relating to the government and security of persons and property, which derive their authority solely from usages and customs of immemorial antiquity, or from the judgments and decrees of the courts recognizing, affirming, and enforcing such usages and customs.”[8]

This definition is consistent with Coke’s thoughts above. Common law is important because a constitution’s construction must be taken in reference to common law.[9] As our constitutions derive from common law; common law is superior to statutory law. Any laws contrary to the Constitution are void.[10] As our founding documents are subject to the superior law within the Bible, this idea would appear to apply to them as well.

Corporation Limits

Corporations are not human beings. They therefore have no rights. Only human beings are sovereign and have rights.

“Sovereignty itself is, of course, not subject to law, for it is the author and source of law; but in our system, while sovereign powers are delegated to the agencies of government, sovereignty itself remains with the people, by whom and for whom all government exists and acts.”[11]

All of America’s governmental units have chosen to incorporate. The Supreme Court has ruled several times that since government has chosen to incorporate, it must follow the same rules as other corporations. And as corporations are not living persons, they can only operate through contracts.

Corporations can also create only code, statutes, rules, and regulations. These are not law, but the equivalent of corporate by-laws. In a word, corporate policy. Such policies apply only to a corporation’s members. Take for example a corporate employee. They must follow policy, or they can face penalties such as being discharged from their position. Member status, such as employment, within a corporation is voluntary. No one can compel you to join a corporation.

This all leads to one big question. How can a corporate government govern a sovereign people? That will be the subject for next time.

Footnotes:

[1] See the Judiciary Act of 1789, https://guides.loc.gov/judiciary-act. Accessed July, 2022.

[2] Wolf, Dan, America’s Original Government, Virginia Christian Alliance, August 23, 2022. https://vachristian.org/americas-original-government/

[3] Library of Virginia, Research Notes Number 12: Virginia Naturalizations, 1776-1929, August, 2009, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/rn12_natural1776.pdf . Accessed August, 2022.

[4] Olney. J., p. 287, A History of the United States, On a New Plan, Durrie & Peck, 1842. This is one example.

[5] Boyer, Allen D. Ed, p. 88, Law, Liberty, and Parliament: Selected Essays on the Writings of Sir Edward Coke, Liberty Fund, 2004.

[6] Wolf, Dan, pp. 14-8, The Light & The Rod: Biblical Governance Corruptions, Living Rightly Publications, 2020.

[7] Boyer, Allen D. Ed, p. 24, Law, Liberty, and Parliament: Selected Essays on the Writings of Sir Edward Coke, Liberty Fund, 2004

[8] Nolan, Joseph R. and Nolan-Haley, Jacqueline M., p. 276, Black’s Law Dictionary, Sixth Edition, West Publishing Company, 1990.

[9] See American Jurisprudence, Second Edition, Volume 16, Section 114.

[10] See Marbury v. Madison, 5th US (2 Cranch) 137, 174, 176, (1803).

[11] See Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 US 356, (1886).