Tas Walker | Creation.com

Geologists have long recognized that history is fundamental to their discipline. Traditionally, the science has been split into two parts—physical geology and historical geology. Before we can make sense of the rocks we need to know what happened in the past—we need a reliable history of the earth.

Long-age assumptions

The problem is that we can’t travel back in time to look, so we have to make assumptions. This problem is such a simple fact, yet it is incredibly profound. Most geologists today assume that the past was much the same as the present. They speculate that the geological processes we see happening now can be extended indefinitely into the past—on and on forever, virtually. This belief is a philosophy called uniformitarianism, and with this assumption they invent a ‘history’ for the earth. The operative word is invention. It is not an observation.

What do we see happening in the present? We see events such as volcanoes, earthquakes, landslides, and tsunamis. These can be large and destructive but compared with the whole of the earth the permanent effects of these are relatively small. In other words, when we extend the present back into the past, we need to imagine these processes going on for millions of years in order to account for all the rocks we see on the earth. That is to say, the need for millions of years of earth history comes directly out of this assumption.

Biblical assumptions

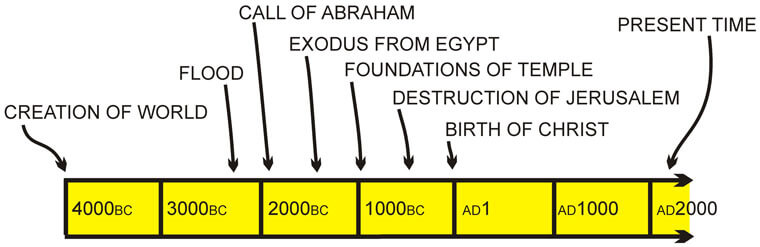

Many people don’t accept this assumption about the past but consider the Bible records accurate history. There are many compelling reasons for adopting this approach, which is the way the pioneers of geological science, such as Nicholas Steno, worked. These people noticed that some events described in the Bible were dramatically different from what we observe today. They used the descriptions recorded in the Bible to guide their thinking about geology. A simplified time line of biblical history is shown in figure 1, and this forms the basis for our geological thinking.

Although the Bible is not a ‘geology’ book, it allows us to understand the big geological picture when we are alert for geological clues. For each historical event recorded we simply ask, “How would this have affected the geology of the earth? What would we look for today?”

From such a study we conclude that most rocks on Earth would have formed during two very short periods of time. The first was the six-day Creation Week, about 6,000 years ago, when the entire planet was produced. The second was the one-year Flood, when the planet was reshaped. By comparison, not much happened geologically in the 1,700-year period between Creation and the Flood, or in the 4,500-year period since. It’s relatively easy to work out the times between these events from the genealogical information provided in the Bible (See Ussher the forgotten archbishop). What that means is that the widely accepted geological assumption of slow and gradual processes over millions of years is not valid.

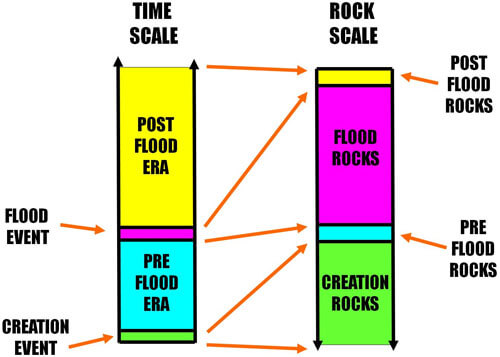

This simple geological model is illustrated in figure 2. The biblical time-line on the left has the most recent time at the top and the earliest at the bottom. The time-scale is divided into four: the Creation event, the Flood event, the pre-Flood era and the post-Flood era.

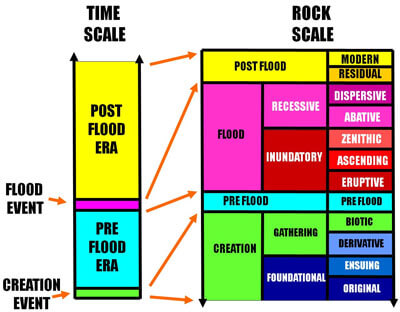

To illustrate how geological process rates varied in the past, we can place another scale alongside the time-scale as shown in figure 2. This is a rock-scale, with the most recently formed rocks at the top, and the earliest at the bottom—the way they occur in the earth. The lengths of the different parts of the rock-scale represent the quantity of rock material found on the earth today and contrast with the lengths of the corresponding parts of the time-scale. For the model to have practical application, the broad framework must be expanded with specific details of the events and processes and their time relationships. This is not difficult. The Flood event, for example, can be divided into two stages: an Inundatory stage with floodwaters rising upon the land, and a Recessive stage with floodwaters flowing off the land.

The model can be divided further, e.g. by splitting the stages into phases. For example the Recessive stage can be divided into two phases: one when the water was receding in wide sheets and later when it was flowing in wide channels. An example of the detailed model is shown in figure 3.

Applying the model

With this geological framework we can interpret the rocks in the field. Every rock on earth today must fit somewhere on this framework because the rock-scale covers the entire history of the earth. The details of how we do this are not covered in this article, but you can find some insights in this article about the basement rocks of the Brisbane area and the one on the rocks of the Great Artesian Basin. We will use the latter as an example here.

Much of the eastern part of Australia is covered in horizontal layers of strata kilometres thick (for details see figures 4 and 5 of the article about the geological history of the Brisbane and Ipswich area) . They extend for more than a thousand kilometres across several states and contain the vast underground water supplies called the Great Artesian basin. Because the sedimentary deposits are so huge, it is most unlikely that they were deposited in either the pre- or post-Flood era. There was not enough time for slow geological processes to deposit such large quantities of sediment. Hence, they must have been deposited in either the Creation or Flood event.

However the sediments comprising the Great Artesian Basin contain fossilised remains of shells, fish, snails, and dinosaurs. Clearly these were not deposited during Creation Week because there was no death or destruction at this time. Thus, these creatures must have been overwhelmed during the Flood.

Animal trackways provide another important clue. Tracks are found at several locations in the sediments, including a mine near Rosewood near Brisbane and at Lark Quarry near Winton in Central Queensland. Tracks mean the animals were alive, so the strata must have been deposited before all air-breathing creatures perished. That was before the world was completely covered with water, during the Inundatory stage.

So, with this simple model and a little reasoning, we have determined that the horizontal layers covering much of eastern Australia were deposited in the first part of the Flood while the floodwaters were advancing. We can use the same approach with other deposits in other parts of Australia. The metamorphosed and folded rocks along the eastern side of Australia were formed earlier in the Flood, and the erosion that formed the landscape was carved as the floodwaters receded. Most of the surface lava flows along the east coast of Australia, including those on Phillip Island near Melbourne and the Glass House Mountains near Brisbane, erupted late in the Flood.

Once we have connected the geology we can develop a geological history of an area that is consistent with the Bible, as illustrated with this geological history of the Brisbane area, Australia. In fact we can develop a preliminary reinterpretation of the geological column (see figure 4 on the article about Wilpena Pound) which will enable us to understand news reports, tourist information and geological reports within the biblical framework.

Changed worldview

Biblical geology provides a vital key to understanding the rocks, which in turn gives us the historical narrative for our world. Such an understanding of geology changes the way we look at the world and of our place in it.

Charts of biblical geological model

These charts of the biblical geological model summarise the basics. The two colour charts can be placed side by side or printed double sided for a hand-out. The black and white chart provides a simple summary.